This week I experimented with our new 32 bit VM to create a viable implementation of 16 bit external calls. This is a really big deal imo, so I'll explain what's happening and why you should care.

The problem

EVM networks impose a hard limit on the size of a contract that is deployed to production. On ethereum this limit is ~24kb of code data.

During development we're free to lift this restriction, the compiler will quietly warn us, but everything will appear to work. As soon as we go to deploy the contract though, all the deployment transactions will rollback and eat our gas for trying.

Even without rain scripts this introduces a nasty tradeoff. Typically the compiler optimisations that make code cheaper to run in terms of gas will make the code itself much larger. Roughly this is because inline code, i.e. code that isn't jumping around with scoped function calls, is the most direct (and so fewer operations that cost gas) way to calculate anything. Things like function calls bring the code size down by introducing reusable chunks of code, but the function call itself always costs some gas as the call must be calculated on top of whatever else it is you're trying to do.

The solidity compiler offers a nice simple runs parameter that lets you specify how many times you expect your contract to be used. If a contract will only be run 1 time (maybe a token vesting/escrow schedule?) then we should make the code itself as small as possible as any code bloat will make the deployment itself cost far more then the running of the code. If a contract will be run 100_000_000 times (an AMM trading algorithm?) then who cares how much the deploy costs, we need it to be as cheap as possible to run, right?

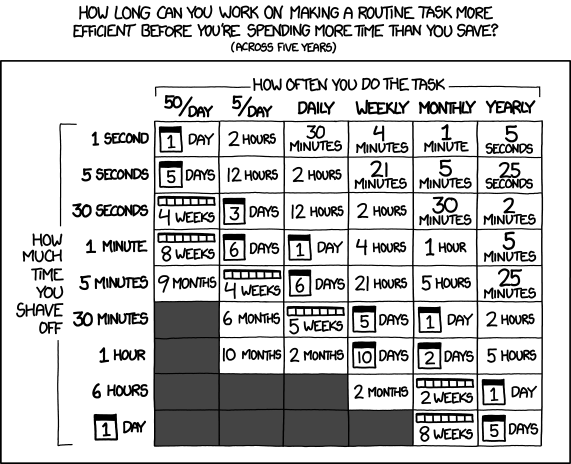

XKCD has a nice comic on a very similar concept. How long you spend automating something to save time relative to doing the thing. It's similar to how much gas you want to spend deploying code vs. running code. Just mentally substitute "time" for "gas" and "code size".

We see this problem even in the old Balancer code that we used in early versions of Rain for liquidity bootstrapping pools. A high value for runs made Balancer undeployable, which is a big issue for an AMM where gas costs directly impact competition for arbs and other trades. Newer versions of Balancer have been refactored heavily but it's a relevant historical example to highlight the problem.

Opcodes reference real compiled Solidity code

Each Rain script is really, really tiny. If you're using the 32 bit version of rain then each opcode in your script is 32 bits, i.e. 4 bytes. That means a 100 word rain script (very complex by current standards) is only 400 bytes long! It's unlikely that a real-world rain script would ever get close to the 24kb contract size limit.

The problem is that the thing that runs the opcodes needs to have the logic for every possible opcode compiled into it, regardless of how popular each of those opcodes are in real scripts. Typically we see that 1 rain opcode represents hundreds of compiled evm opcodes, which is great for expresssivity, but does put pressure on the size of the VM contract.

Obviously we've made it work so far, we've got launchpads, order books, NFT mints, ERC20 mints, etc. all happily using the VM, but here are some goals for the near future:

- Support "unlimited" opcodes so we can interface with more than just the base ERC20/721/1155 standards, e.g. price oracles/TWAPs, vaults, etc.

- Ability to make judgements per-VM contract on whether some opcode is "hot" so must be as cheap as possible vs. "rare" and so we'd prefer not to bake it into the VM itself

- Inheriting the VM via.

is StandardVMshould weigh in somewhere around what people already expect for an off-the-shelf Open Zeppelin token (e.g. ~4-6kb based on current compiler settings in the rain repo), so we want to knock off 40-50% relative to status quo

One nice thing about VM-ifying a contract is that it tends to remove the need/desire for a lot of boilerplate checks and balances in the surrounding Solidity. One example of that is the current rTKN implementation which supports native tier gating in the token contracts, so there's code that loads and checks recipients of tokens against a tier contract on each transfer. Sounds good, but in reality this is a useless historical artifact, the Sale itself has opcodes that can access-gate purchases directly in the sale price curve! As this has been exposed in the sale via. opcodes I'm free to rip out all tier related logic from the associated rTKN contract. This makes the sale/rTKN overall system simultaneously leaner and more flexible.

At some point on the leanosity spectrum we can say that is StandardVM is code-size neutral for "typical usage". That is to say, that adding in opcodes and associated eval machinery is no larger than the code you would have written anyway just to enforce sane usage and avoid hacks/exploits.

The problem will get worse without a systematic approach

Right now we can probably be ruthless and cut out several opcodes. Do we really need to ship 1kb for the debug opcode into production? Could add and saturating_add be merged? Do we need all the various ways to scale fixed point decimals or would one method suffice?

This would already cut code bloat by a meaningful number, around 1-2kb. I'll be doing a solid cull very soon, but this is a one time thing. We have a shopping list of at least a dozen new opcodes we'd like to add right now:

- Several 4626 vault functions

- Chainlink oracles

- Uniswap oracles

- Open Zeppelin contract access control and ownership

- Gaming oracles reporting the outcome of a match/tournament

- NFT marketplace data

- Governance information, voting rights/results, etc.

- Lending, defi data, etc.

A lot of these will only be used by 1% or less of all scripts out there, but for those scripts these opcodes are an absolute deal maker/breaker.

We currently have just over 40 opcodes total bringing a base VM to a bit under 12kb. I'd estimate with around 150 opcodes we could read basically all onchain data that can be considered relevant to the zeitgeist and is accessible via. some roughly standard-ish interface. We can hugely leverage the existing culture of "money legos" where smart contract writers fight hard to represent concepts as standard interfaces. Massive win for web3 over web2 wherein every company wants and builds their own snowflake API into their corporate database.

The solution

Here I'm obviously going to present external calls as a/the solution to the above. After all it's the title of the blog post.

High level the solution is that we run "hot" opcodes in the VM contract and run "rare" opcodes on some other shared public good contract. All the external opcodes are treated identically from the VM's perspective, so the only code bloat to the VM contract is one new opcode to send and receive data to/from the external contract, then we can delete all the code for all the opcodes that we let the external contract handle.

The external contract has no storage/state of its own, can't access the VM contract/state, and can only process opcodes that are purely input/output. A great example of this is ERC20 balanceOf. A VM can forward a token address and token holder address as raw uint256 values from its VM stack to the external contract, which can interface with the ABI of the actual token contract, and return the balance to be put on the VM stack.

If this sounds familiar, it's probably because this is how libraries with external functions and delegatecall, etc. already work. There's nothing truly new being presented here, more an explanation of and implementation for leveraging existing blockchain design patterns in a rain script context.

As we now have 4 byte words in rain scripts, we have 2 bytes for the VM function pointer to the external call opcode, which then has 1 byte to encode the index of the external opcode, and 1 byte to encode the inputs/outputs count. The inputs are taken from the VM stack at runtime and inputs/outputs are used for integrity checks at deploy time. On the receiving side we have all the function pointers to opcodes available to be read by index in O(1), then the appropriate opcode is run with an uint256[] of inputs and uint256[] of outputs. The outputs are passed back to the VM and added to the stack.

With a full byte for external opcode indexes this gives us 256 possible opcodes, which is probably more than can even fit in a single external contract. There's the potential to support multiple external contracts as "rare" and "extra rare" if we somehow exceed the 256 opcode limit, all we need to do is reserve 1 extra bit in the operand (likely cannabilizing the outputs length or even taking 1 bit off the local function pointers).

Every supported opcode can be then written as a library in terms of integrity check, internal execution, external execution. This way VM contract writers are free to include any opcodes that are "hot" for their contract and hand the rest over to the external contract. Every VM can then offer equivalent functionality but with its own domain specific code size and performance profile. For example, we can say a "tier combiner" needs all the tier logic on the hot path but maybe an "NFT mint" can afford a little extra gas for certain tier operations.

The cost

External call looks identical to call from the VM's perspective, at least in terms of handling inputs/outputs on the stack, but for a single opcode only.

If we compare it to something concrete like that we can meaningfully clock our gas costs.

Using data from early experiments, call is about ~0.5-1k gas and external call is about ~2-2.5k gas. EVM charges extra the first time an external contract is loaded, so it's about double for the first external call in any transaction. I'm giving ranges because depending on how you compile and measure it, and what hard fork you are using, the numbers can change. Most scripts are going to have fewer than 5 external calls, so let's call it ~10-15k overhead for moderately complex workloads (zero overhead on the hot path) in exchange for "unlimited" opcodes.

There's probably some optimization that can be done, but a lot of the cost comes simply from the overhead of passing data between contracts. This may be reduced in the future as the gas costs change over time and technology improves.

One little trick that can bring the cost down a lot for a script is to use the stack opcode to duplicate previous external calls for 1/10th or less of the gas cost. It's possible to front load all the external calls then copy them into place for the subsequent calculations. The rain tooling even knows how to surface this to the end users in a readable way with tagged script data.

Dialects

In a world where any VM contract can have any combination of internal and external opcodes, end users have no hope of reading the raw bytes and knowing what is going on. They never really did though, there's always been a javascript tool in between that translates an opcode like 0x02ad0003 into "add 3 numbers".

This javascript layer is also completely configurable. There's a set of metadata that translates opcodes to something human legible, and a mutable simulator that maps opcodes to closures that can run to demonstrate VM outcomes.

Until now most of the work in Rain has been to take a "standard" set of opcodes, wrap them in some well known functionality and deliver it to end-users via. some well known factory.

This approach helps get the basic point across but also introduces some pain points:

- Centralisation around the factory trust model and maintenance

- "Too bloated" for some use cases and simultaneously "not enough" for others

- Centralisation of the definition and inclusion of opcodes

Moving forward there will be much more emphasis on "dialects". Perhaps sometime in the future we'd even define a portable .rain file format that has metadata in the header, IDE support and can even move between EVM and non-EVM chains.

This does however introduce the very real and likely possibility of malicious dialects. Well, "introduce" is perhaps the wrong word as anyone can create a malicious fork of Rain right now. It certainly lowers the barrier to entry for scammers though, which is one of the main things Rain set out to counteract, not to enable.

Imagine though, taking the idea behind token lists and applying it to whole dialects and associated factories. This is the truly decentralised version of Rain, where a dialect is just another form of web3 curation and users decide for themselves who and what to trust.

The difference however, is that being able to trust a token vs. being able to trust an entire dialect of tokens, is a whole new level of abstraction.

Just as today anyone can make a token for their network/project/community/company/self, in the near future anyone can make their own high level smart contract language and deploy it onchain. Total permissionless expressivity ✌️

And how does a dialect form? Clearly someone has to code it. What does that look like?

Here's the current WIP implementation of add with both internal and external definitions, as well as integrity checks.

// SPDX-License-Identifier: CAL

pragma solidity ^0.8.15;

import "../../runtime/LibStackTop.sol";

import "../../../array/LibUint256Array.sol";

import "../../runtime/LibVMState.sol";

import "../../integrity/LibIntegrityState.sol";

import "../../external/LibExternalDispatch.sol";

/// @title OpAdd

/// @notice Opcode for adding N numbers.

library OpAdd {

using LibStackTop for StackTop;

using LibIntegrityState for IntegrityState;

using LibExternalDispatch for uint256[];

using LibUint256Array for uint256;

function _add(uint256 a_, uint256 b_) internal pure returns (uint256) {

return a_ + b_;

}

function integrity(

IntegrityState memory integrityState_,

Operand operand_,

StackTop stackTop_

) internal pure returns (StackTop) {

return

integrityState_.applyN(stackTop_, _add, Operand.unwrap(operand_));

}

function intern(

VMState memory,

Operand operand_,

StackTop stackTop_

) internal view returns (StackTop) {

return stackTop_.applyN(_add, Operand.unwrap(operand_));

}

function extern(uint256[] memory inputs_)

internal

view

returns (uint256[] memory outputs_)

{

return inputs_.applyN(_add);

}

}

The extern definition can probably be streamlined with its own form of applyFnN but even without that, building a custom opcode is only ~10 lines of code + ~40 lines of boilerplate.

Actions

If you are a developer, checkout the external call branch and try writing an opcode :D

Everyone else can think about and plan their own dialects too. It's just as reasonable, perhaps even more reasonable, that social entities coalesce around new ways of thinking and expressing than tokenising and transferring.

Also, join the telegram group https://t.me/+wEISp4a48V5mOTJk. More the merrier.